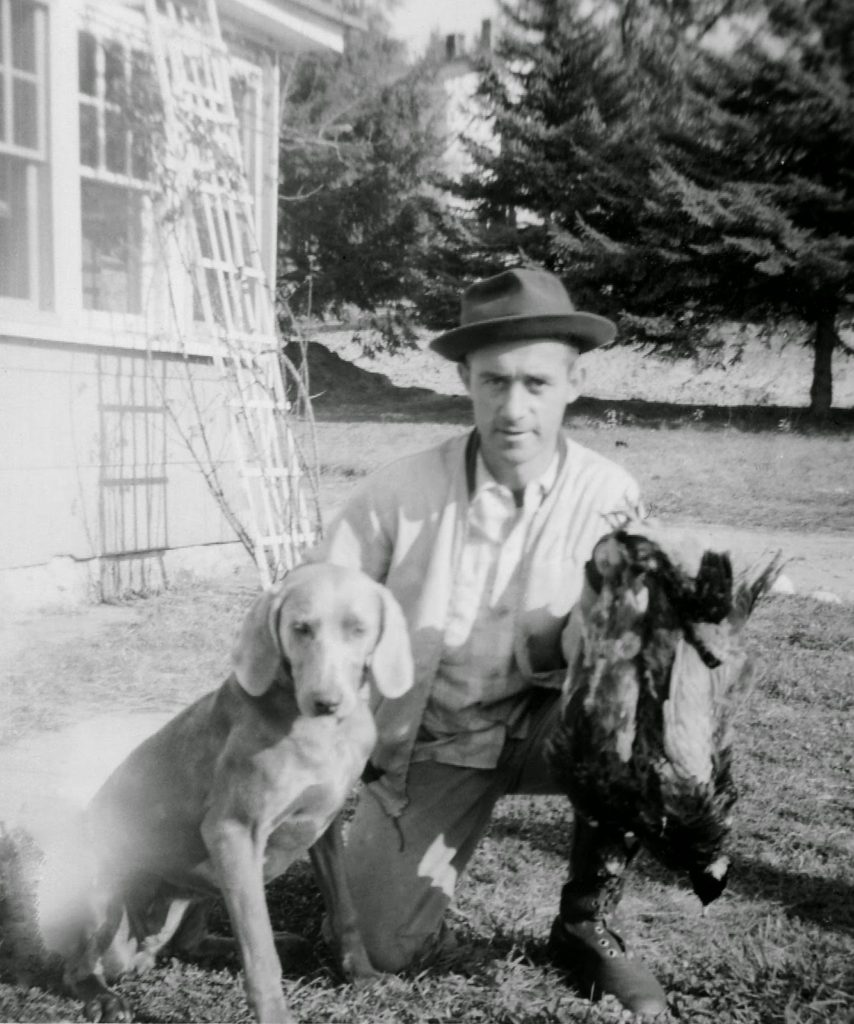

In prior blogs I’ve written about the allure fly angling has had on me since my early youth. It is rooted in New Hampshire. My earliest memories are of our home on Benton Road in Hooksett, New Hampshire. Benton is a rural-like road, and Hooksett is just north of Manchester. Our backyard was the New England woods all the way to the Merrimack River. The Merrimack is a large, powerful river, and its upper reaches still support Atlantic salmon as part of the Merrimack River’s Anadromous Fish Restoration Program. There is a small brook, Benton Brook, that is north of our old house towards the Londonderry Turnpike (I believe it is now called Dalton Brook). The brook drains into the Merrimack, and on the way it skirts along the backside of commercial property on the west side of the Turnpike. One of those properties had a little man-made reservoir that contained stocked rainbow trout back in the early 1960s. As the crow flies, the Merrimack was less than a half-mile from our house, and the meandering course of the little brook was about a mile long from where it passed under Benton Road. Also behind our house, in the thick of the Merrimack Valley woodlands, were other shallow ponds and swamps. I recall skating on Maureen’s Pond on double-rail skates in the winter, and that was without adult supervision. As a child I never realized how close we lived to the mighty river; the thick woods made it seem so far away and mysterious. Images of my brothers Neal and Bruce emerging from the woods with water moccasin snakes, cottontail rabbits, grey squirrels, and even a porcupine are still vivid in my memory. At the edge of our property, abutting the woods, my father had a dog kennel. Dad raised Weimaraners, training them for bird hunting. We had a chicken coop where we harvested fresh eggs, and a garden that grew fresh melons and vegetables. I recall the wonderful cucumber sandwiches mom would slice up, as well as the trouble I got into from secretly dipping wild rhubarb in the sugar bowl, the pink stain being the convicting evidence. I may be suffering from selective memory or romanticism, but I think that was a wonderful way to start a life, and I’m thankful for those beginnings.

Dad died in 1959. I was three years old. I missed the opportunity to grow-up under my dad’s guidance. As good as my older brothers were to me, there is no substitute for your dad. We all made the best of it. Although too young to fish with my father, I do recall watching my brother Bruce fish the little brook down by the Turnpike. Bruce would catch little brook trout on worms we dug up from our garden (which fly anglers refer to as garden hackle). I recall once when we were following the little brook to the river, we snuck up on the man-made reservoir so that the commercial proprietors wouldn’t see we were fishing their little pond. Bruce caught a rainbow trout, the first I ever saw. I remember another time hiking along the brook all the way to the Merrimack with Bruce. It seemed like a long, mystic adventure, but in reality it was a short hike in one of the most populated areas of New Hampshire. There were train tracks that ran on the eastern side of the river, and I recall Bruce placing a silver dime or nickel on the rail when a train was coming. The wheels of the train flattened those coins into substitute sinkers that could be folded and crimped on the line. I have no doubt that those adventures along the brook to the Merrimack planted the seeds of my favorite hobby.

But the move to Las Vegas, Nevada in the middle of the third grade considerably slowed my development as an outdoorsman. Transplanted from the wooded Merrimack Valley of New England to the Mojave Desert of southern Nevada was quite a shock. While my brothers and I adapted, I’m sure we all felt that we might never hunt or fish in the outdoors again. Within five or six years Bruce fled Las Vegas for the coastal mountain hills of Ojai, California, where he’s become known as the resident Ojai Naturalist. Bruce is quite the fisherman in his own right, and is well versed with the trout of southern and central California. He, too, made the transition from bait and hardware to fly fishing along his journey, and I hope I had some influence with that.

As mentioned in other blogs, Neal took me under his wing after Bruce moved away, introducing me to firearms, hunting, and fishing. Neal’s camping invitations always excited me. We drove in his 1968 Toyota Landcruiser throughout the snow-capped timber forests of Nevada. We explored mountain ranges like Schell Creek near Ely, Toiyabe near Austin, and Jarbidge north of Elko near Idaho. In Utah Neal introduced me to the Fish Lake National Forest in the Tushar Mountains near Beaver. He told me about his fishing success at Beaver Dam State Park near Caliente, Pine Valley and Enterprise reservoirs north of St. George, and of the alpine lakes of the Ruby Mountains near Elko. All places that I have trekked through because of him, while catching a trout or two.

Hunting with guns and bow-and-arrow had a primitive lure. I thoroughly enjoyed hunting in the outdoors. There is an adventurous thrill to tracking, calling, and stalking wild game. Something stirs in the soul of a man, likely the “hunter-gatherer” instinct that God placed in boys and men. I enjoyed the shooting and the thrill of the hunt, but the “cleaning” of game was something that I tolerated but never really warmed to. But of all the cleaning, I thought trout were the easiest. Perhaps that encouraged a higher degree of interest in trout fishing.

As I emerged from my teenage years, my affection for the outdoors and my interest in hunting and fishing began to focus on fly fishing. Knowing that my father and my oldest brother practiced the craft certainly had an influence. But it was more than that. Neal was an avid reader, and he had a small library on the outdoors. He had technical books like Ormond’s “Complete Book of Hunting,” Rutstrum’s “North American Canoe Country,” and Shaw’s “Fly-Tying,” but he also had books that were descriptive of the outdoorsman’s explorations like Bergman’s “Trout.” And not only did the descriptions of the practices, techniques, and voyages of the outdoor crafts capture my imagination, the books also introduced me to the art of pen and ink drawings. I was particularly captivated by the scratchboard style of Les Kouba who illustrated many of Calvin Rutstrum’s books. But Neal also had books that described the adventure of hunting and fishing in ways that were romantic to me. By “romantic” I mean their literature and art stirred my imagination, emotion, and introspection. Often the outdoor books in Neal’s library celebrated nature and freedom of the spirit. I found that fly fishing literature aptly fit my idea of romantic adventure.

Although Neal introduced me to the finer aspects of being an outdoorsman, he never seemed to have the patience to teach me fly angling. Fly rods are somewhat delicate, especially compared to guns and other hardware, so perhaps he was concerned I’d break his equipment. Or maybe he knew fly casting was not something easily learned and he did not have the forbearance or tolerance to instruct a young boy. Whatever Neal’s reason, I realized that my brother was not going to teach me to fly fish. So after paging through Neal’s book library and daydreaming of my own adventures, I decided to pick up a few instructional books and order my first fly rod through a catalog (likely from one of the last Herter’s catalogs).

At that time I was in college, and I usually spent my weekends hiking with my friend Kevin. Our excursions throughout Clark County eventually brought us to Cold Creek in the northwestern portion of the Spring Mountains. A topographic map eventually revealed a blue line that was Cold Creek in the foothills on the northwest slope of the mountain range. The creek gushed from a cave-like spring in what otherwise would have been described as an arroyo. The upper 150 yards of the creek were not choked by willows, and one section was known to have wide beds of watercress with narrow channels undulating through it. In the late 1970s Cold Creek was entirely undeveloped, and it was rare to see anyone exploring in the area. In fact, a weekday visit guaranteed absolute solitude. As I reflect, it must have reminded me of the little Benton Road brook. While exploring the creek Kevin and I noticed small fish darting for cover whenever we approached as hikers (as opposed to stealthy fishermen). I assumed they were trout, but I was not sure. Later on I stumbled upon a source indicating the Boy Scouts from nearby Camp Bonanza had stocked the creek in the past, and since the creek was perennial I assumed the trout were reproducing and self-sustaining.

One of my first fly fishing book purchases was Joe Brooks’ “Complete Book of Fly Fishing.” Brooks started his storied fishing career in Maryland, but he eventually fished all over the world while emerging as the most influential fly fisherman of the 1960s and early 1970s. He pioneered fly fishing for striped bass, bonefish, and other salt water species, but his love was trout fishing and it eventually led him to settle in Montana. He died of a heart attack while fishing Montana’s Big Hole River. His last book, “Trout Fishing,” opened with a twenty-five page chapter on the history of trout fishing which I found fascinating.

It was Brooks’ guidance that encouraged me to purchase my first rod, an eight and one-half foot Fenwick rod for a seven-weight line ordered through a catalog, and I included a fly tying kit for good measure. He described it as the best all-round rod for western fishing, and he was likely correct if you were fishing large western rivers for trout and salmon or largemouth and striped bass. I did indeed live out west, it was just that I lived in the southwest Mojave Desert where nearby trout streams were but tiny brooks compared to the big Montana watercourses. Knowing no better, I took that large seven-weight rod to Cold Creek one afternoon in 1977. I was surprised and delighted to catch several little rainbow trout and one brook trout. They were my first fish caught on a fly rod, and with a dry fly I hand-tied myself. The flies were ugly and nondescript, sloppily lashed on size twelve hooks. No respectable trout should have even considered eating my hand-tied flies, but in 1977 these might have been the first artificial flies the Cold Creek trout had ever seen. They attacked with abandon and disregard. All I had to do was find a way to alight them someplace on the water. The creek was shallow, and they would dart from afar to reach my creations. The brook trout, as I recall, struck from under the watercress as the dry fly floated on the ribbon of water snaking through the watercress. It was a short cast of less than thirty feet, and most of the seven-weight line rest upon the watercress. The fly didn’t travel but six inches before it was gulped. As soon as the diminutive trout struck I launched him into space with that heavy rod. Turned out he was not quite seven inches long, and with no water between him and the floating dry fly he was easily levered right out of his water element.

As stupid as that might sound to an experienced fisherman of any method, it was a turning point for me. I didn’t know then the ancient history of the fly angling craft, but I knew it was an amazing experience to catch a trout rising to a dry fly in a stream. Even with what would be considered a heavy fly rod for trout, to be able to cast a fly of my own making to a spot on a small creek in such a way as to entice a wild trout to mistake it as a natural food source, well it was most electrifying. The experience made me fantasize fishing a Montana river beside Joe Brooks, casting to five pound brown trout that were rising to stone flies laying their eggs in the river. If catching a parr sized trout could be that amazing, I knew a larger fish would enhance the experience exponentially.

Most angling historians think angling dates to before the Shang Dynasty, perhaps to Noah and the flood. Certainly the tools where present in China during the Bronze Age of civilization, where ancient manuscripts mention silk lines, thornwood rods and primitive metallurgy. But most agree that Roman writer Claudius Aelianus (known as Aelian) deserves credit for the first description of fly fishing. Brook’s “Trout Fishing” and Schwiebert’s “Trout” contain exactly the same extract from one of Aelian’s manuscripts, dated around 200 B.C., which is the first known description of the use of an artificial fly to catch a fish.

I have heard of a Macedonian way of catching fish; between Beroea and Thessalonica runs a river called the Astraeus, and in it are fish with speckled skins; what the natives of the country call them you had better ask the Macedonians. These fish feed on a fly peculiar to the country, which hovers on the river. It is not like the flies found elsewhere, nor does it resemble a wasp in appearance, nor in shape would one justly describe it as a midge or a bee, yet it has something of each of these. In boldness it is like a fly, in size you might call it a midge, it imitates the colour of a wasp, and it hums like a bee. The natives generally call it the Hippouros.

These flies seek their food over the river, but do not escape the observation of the fish swimming below. When then the fish observes a fly on the surface, it swims gently up, afraid to stir the water above, lest it should scare away its prey; then coming up by its shadow, it opens its mouth gently and gulps down the fly, like a wolf carrying off a sheep from the fold or an eagle a goose from the farmyard; having done this it goes below the rippling water.

Now though the fisherman know of this, they do not use these flies at all for bait for fish; for if a man’s hand touch them, they lose their natural colour, their wings wither, and they become unfit food for the fish. For this reason they have nothing to do with them, hating them for their bad character; but they have planned a snare for the fish, and get the better of them by their fisherman’s craft.

They fasten red (crimson red) wool around a hook, and fix on to the hook two feathers which grow under a cock’s wattles, and which in colour are like wax. Their rod is six feet long, and their line is the same length. Then they throw their snare, and the fish, attracted and maddened by the colour, come straight at it, thinking from the pretty sight to get a dainty mouthful; when, however it opens its jaws, it is caught by the hook and enjoys a bitter repast, a captive.

Claudius Aelianus, 200 B.C. Manuscript

And though there would be a certain fascination knowing that the sport of fly fishing pre-dates the life of Jesus Christ, it would not be enough for me. History was not my favorite school subject, but I do find it interesting that fly fishing has a very rich history which can be followed and appreciated. It can be traced from Aelian to Charlemagne and Berners in the Medieval Period, then Walton, Nowell, and Donne of the Classic Age, then through the nineteenth century Renaissance and up to the more modern advancements by Halford, Skues, and Gordon as the sport evolved to employ more scientific knowledge. (Those looking for a quick history lesson should try FlyFishingHistory.com.) Despite the monumental impact that the acceleration of science and technology have had on equipment and technique these past forty years, I still value how elemental and basic the roots of the sport are: catch a fish by fooling it with a hook adorned to resemble an insect on the end of a line cast into the water with a stick. It seems like pretty simple stuff that dates back a couple thousand years.

But if only it were that simple. The complexity of modern technology and techniques for fly fishing can be overwhelming. I have written a blog for beginners on the subject of assembling basic fly angling tackle. It does not address casting, fly presentation, or other elements of the craft, but only basic equipment. As I look back on that writing I find it is likely daunting for the average beginner. And yet it is simple. In his preface to “Complete Book of Fly Fishing,” Brooks writes:

Unfortunately there has been a tendency among writers to make fly fishing sound difficult and thus many a would-be fly fisherman has been diverted from this most satisfactory sport. The purpose of this book is to show that with a little practice, fly fishing is, not easy, but quickly learned, and that once learned it pays dividends such as no other type of fishing can offer.

Joe Brooks, “Complete Book of Fly Fishing”

After my first Cold Creek fishing experience in my junior year of college, I began to collect my own fly fishing library. In the early years, in addition to Brooks’ writings, there were other technical books like Ovington’s “Tactics on Trout,” Marinaro’s “In the Ring of the Rise,” Wulff’s “Lee Wulff on Flies,” and Schwiebert’s “Matching the Hatch” as well as his 1,600 page, two volume epic “Trout.” Marinaro’s book, published in 1976, contained the most revealing photos of brown trout rising to flies on his beloved Pennsylvania spring creeks. Likewise his underwater photos of dry flies and their appearance to the trout’s eye, describing what the fish sees and does not see, was extremely helpful to my understanding of trout feeding behavior. It was a work that really opened my thinking to the science of catching trout on a dry fly. Recently I was reading about Marinaro on the back flap of the book, and I smiled upon learning he was a retired corporate tax specialist… no wonder his meticulous attention and study of the details of brown trout rising to dry flies.

Later, as I gained reasonable skill in the craft, I gravitated toward those works that describe the experience and condition of fly fishing rather than its technical “how to.” So now I often enjoy a read of Haig-Brown’s “Return to the River,” Lyons’s “The Seasonable Angler,” Maclean’s “A River Runs Through It,” Gierach’s “Trout Bum,” and Lyons’s “Hemingway on Fishing.” And when I want to connect more to the history of the art I pull out my copy of Izaak Walton’s “The Compleat Angler.” Walton wrote in the latter half of the 1600s. By the end of the seventeenth century, a scientific revolution had occurred such that science had become an established mathematical, mechanical, and empirical body of knowledge. By then the likes of Galileo, Descartes, Pascal, and Newton had become recognized as noted scientists. Interestingly, Walton wrote:

For Angling may be said to be so like Mathematicks, that it can ne’r be fully learnt; at least not so fully, but that there wil stil be more new experiments left for the trial of other men that succeed us.

Izaak Walton, “The Compleat Angler”

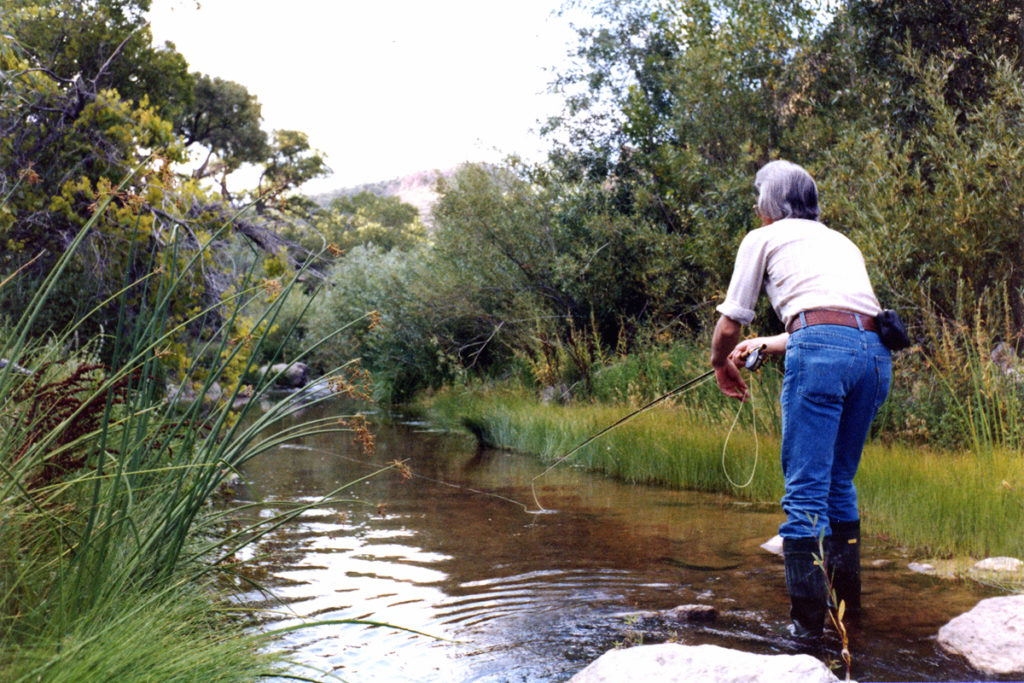

I don’t think the sciences of entomology, hydrology, and ichthyology have really sunk into my brain over these thirty-plus years, any more than the technological development of the line, leader, and fly. But I do know that every time I’m on a stream trying to locate a trout, figure out what it will accept as food at that specific time and place, and execute a cast such that the fly is presented to his liking, I feel an adrenaline surge at that very moment the tug and pull of the trout’s weight and the force upon the line runs through the guides up to the fingertips of my left hand. It can be at once a physical, intellectual, and spiritual experience.

The life of a fly fisherman is seasonal. The cycle of the weather seasons certainly makes it so, but the seasons of a fisherman’s life also dictate what will be offered and taken as father time marches on. I’m not the physical specimen I was in my thirties and forties, so I’ll not be climbing the high Sierras or wading the depths of a raging northwest steelhead river in the remainder of my life. But I know the sensation of catching a trout on the fly, and that remains the common thread throughout my fishing life. I appreciate how Lyons describes his addiction to the art of fly fishing in “The Seasonable Angler“:

There is, or should be, a rhythmic evolution to the fisherman’s life (there is so little rhythm today in so many lives). At first glance it may seem merely that from barefoot boy with garden hackle to fly-fisherman with all the delicious paraphernalia that makes trout fishing a consummate ritual, an enticing an inexhaustible mystery, a perpetual delight. But the evolution runs deeper, and incorporates at least at one level an increasing respect for the “event” of fishing (I would not even call it “sport”) and of nature, and a diminishing of much necessary interest in that fat creel.

But while the man evolves – and it is trouter, quite as much as the trout, that concerns me – each year has its own rhythm. The season begins in the dark brooding winter, brightened by innumerable memories and preparatory tasks; it bursts out with raw action in April, rough-hewn and chill; it is filled with infinite variety and constant expectation and change throughout mid-spring; in June it reaches its rich culmination in the ecstatic major hatches; in summer it is sparer, more demanding, more leisurely, more philosophic; and in autumn, the season of “mellow fruitfulness,” it is ripe and fulfilled.

And then it all begins again. And again.

I am a lover of angling, an aficionado – even an addict. My experiences on the streams have been intense and varied, and they have been compounded by the countless times I have relived them in my imagination. Like most fishermen, I have an abnormal imagination – or, more bluntly, I have been known to lie in my teeth. Perhaps it comes “with the territory.” Though I have been rigorous with myself in this book, some parts of it may still seem unbelievable. Believe them. By now I do. And why quibble? For this is man’s play, angling, and as the world becomes more and more desperate, I further respect its values as a tonic and as an antidote – on the stream and in the imagination – and as a virtue in itself.

These then are the confessions of an angling addict – an addict with a “rage for order,” a penchant for stretchers, and a quiet desire to allow the seasons to live through him and instruct him.

Nick Lyons, “The Seasonable Angler”

And so to my fellow fly fishermen on this 2011 Father’s Day, may you be thoughtful and satisfied as you soak in the offerings of nature. May you continue to experience those special trout that feed in lies that are difficult to reach and drift. May you experience the feel of that perfect cast, and the electrifying strike of a “good” fish. Most importantly, may you always remember the Creator of it all so that this angling art does not become a false idol in your life.

Wow…..brother-law-Mark……I never knew all of this. Now I do.

Promise we shall watch “A River Runs Thru It”!

Congratulations SIL Jeannie! You are the first, and currently the only, person to post a comment on this intriguing and moving story of how I came to become a fly angler. I am forever grateful I have at least one relative that likes to read these stories with hidden meanings about life, love, and adventure… LOL